“ Perhaps after a while she starts daydreaming,

and imagines that it’s him who’s waiting for her call.

And who knows, who knows, she wonders, is there any difference

between a man waiting and a woman waiting? ”

Nina’s first solo show.

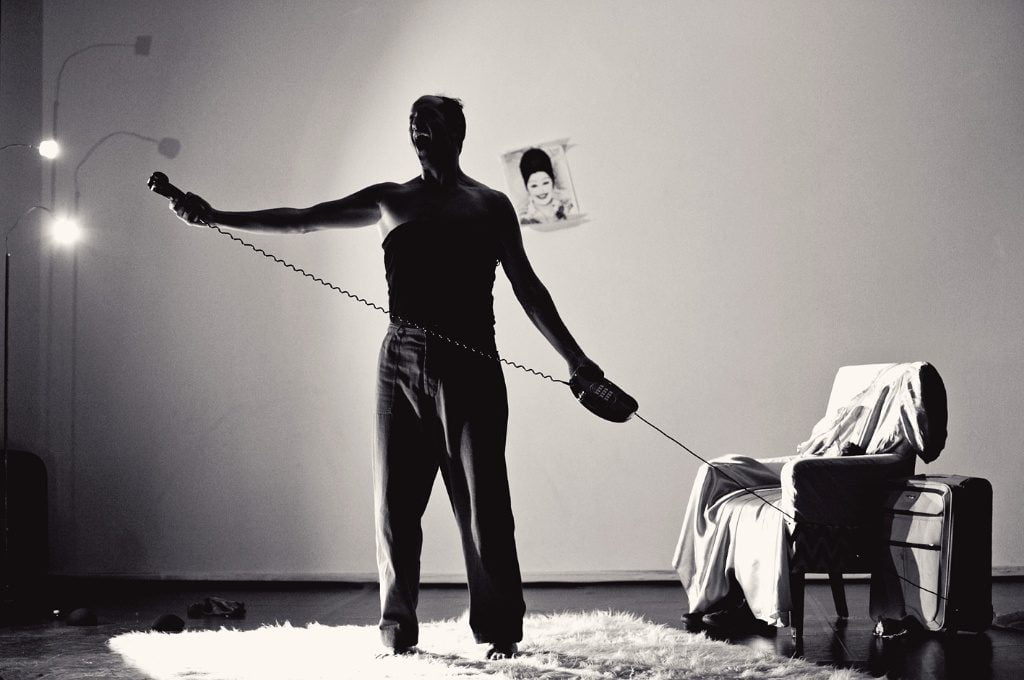

In the suspended dimension of a room, a female character is chased, dismantled, searched between the lines of the text, in a journey between man and woman, love and waiting, celebrated muses and ordinary housewives.

The English-language version of the show debuted in 2018 at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, with the same performer and the translation of Maggie Rose.

This tragicomedy goes right to the heart of drag, putting love and creativity under the spotlight, with all the frustration and exaltation they may entail.

Two very different female figures: Alma Mahler is a free, independent soul, almost the personification of art itself; the other woman is mediocre, without heroism or an identity. In both cases, the focus is on a man’s violent behaviour towards a woman.

Cocteau and Kokoschka try to create an imaginary woman, to control them with their gaze, the first through writing, the second through art. Onstage, an actor attempts to attain an elusive female essence, even if he knows he will never get there. His search for Alma, or for love, or for the perfect form to represent a woman, overlap and intertwine. The solitude brought about by the love and the solitude of the artist go hand in hand, alive in the very same room.

For this show, we had we had the pleasure of collaborating with Daria Deflorian, actress, author and director, who put the research on scenic languages and the relationship between performer and audience at the center of her work.

ALMA, a Human Voice

written and performed by Lorenzo Piccolo

director Alessio Calciolari

assistant director Ulisse Romanò

tutor Daria Deflorian

translated by Maggie Rose

scene and costumes Rosa Mariotti

lights Andrea Violato

photographer Valentina Bianchi

production Aparte – Ali per l’arte

co-production Danae Festival

with the contribution of Fondazione Cariplo – project fUNDER35

selected by NEXT 2016 – Lumbardy Region and Kilowatt Festival

thanks to IT festival – Open IT project, Sorellanza

★★★★ Eddie Harrison, The List

Alma, A Human Voice is unlike anything I have ever seen.

I would keep an eye out for Nina’s Drag Queens.

★★★★ Greta April, Arthur’s Seat

A turbulent, disconcerting examination of love and loss, and how quickly we can spiral into utter disorientation.

★★★ Kirstyn Smith, Marbles Mag

Lorenzo Piccolo offers eloquent images of a male figure in full flight from stereotyped masculinity. (…) Alma is visually vivid, and full of a profound sense of escape from the bonds of a kind of masculinity that prefers to feel nothing rather than risk the pain of Cocteau’s heroine, and that believes a living, breathing woman can somehow be replaced by a doll.

★★★ Joyce McMillan, The Scotsman

I’m delighted by what I see here: a very clever and beautifully realised exploration of the tropes of ‘woman as victim of love’ and ‘woman as muse’. Dorothy Max Prior, Total Theatre

Lorenzo creates moments of statuesque stillness which take your breath away. (…) A stunning piece of theatre.

Brian Butler, Gscene

Stirring visual and aural imagery. (…) Lovely, sensitive.

Caitlin A Kearney, The Skinny

A show in which irony competes with aesthetics.

Tom Wicker, Fest

Surprise! Nina’s Drag Queens have accustomed us to a kind of excess, exquisite costumes, over-the-top tricks, dizzy stilettos. Instead in this monologue everything is measured, composed, ironic, delightful. Lorenzo Piccolo wearing his “good boy face”, without a touch make up, reenacts two tragic stories with enchanting humour. He deploys a minimum of drag queen tools, with admirable lightness and vitality. Simply an hour of pure pleasure.

Fausto Malcovati, Hystrio

MAGGIE Why the title Alma, the Human Voice?

LORENZO It is a summary of the two starting points of the show: Cocteau’s “Human Voice” and the figure of Alma Mahler. The Italian title, “Vedi alla voce Alma” is a sort of untranslatable word game that sounds like “look up the entry Alma”, but also contains the word ‘Voce’ (Voice).

M What was the seed that kickstarted your play, Alma?

L At an exhibition in Vienna, I saw a picture of Alma Mahler’s doll – the doll Oskar Kokoschka had built after she left him. She was lying on a sofa, peaceful and scary, immersed in a timeless solitude. Somehow she reminded me of the abandoned woman in “The Human Voice” … so I tried to weld together these two images.

M Like Godot, it’s a play about waiting. Beckett wrote about men waiting in very different circumstances, you choose women, who are feeling absolutely desperate because of a relationship gone wrong.

L I guess that time is a central issue in theatre, as theatre is a real-time experience shared between stage and audience, but of course a symbol as well. So for me it is a really funny but also honest question: how can I let time pass on stage? How can I represent waiting?

M You ask the audience at one point is there a difference between a man and a woman waiting for an unfaithful lover. In your role of man\woman, using drag techniques, you seem to place yourself in excellent position to try and answer this question.

L I think that the interesting thing is that you can ask yourself this question. It means that, in our mind – and in our society – there are things for men and things for women, or, at least men-ly ways and woman-ly ways to do things…

The question also give me the opportunity to say that, as a drag, I’m not exactly interested in representing a woman. Femininity is just something that I love as a theatre game, an expressive key. Being a man playing a woman, I put myself somewhere in the middle, as you say. In particular in Alma this happens a lot and it is very fluid: I am the nameless woman on the phone, but also Oskar, Alma as muse, Alma as a doll, an actor, Jean Cocteau, a milliner… I just express human nature.

M You interweave two other story lines into Alma. Cocteau’s Human Voice, in Ingrid Bergman’s splendid interpretation, and the Alma Mahler-Kokoschka story. What kind of writing process enabled you to achieve this?

L I worked on the two stories separately, so much so that every now and then I asked myself if I wanted just to rewrite the Human Voice, or just to tell a story about Alma’s doll.

With Cocteau’s play, I feel a deep bond, a love-hate one. In a way it is something very old and old-fashioned, in others it really is something that never changes: violence in human relationships, unrequited love, lies and so on. So, trying to decide if I liked this one person, one act play or not, I began a dialogue with it and I started taking just the stage directions, which were sometimes more interesting for me than the play itself. The lip-sync provided the rest and gave me one more chance to engage in a dialogue with the “living” material.

With Alma’s story, the writing process was very simple. I just wrote down the facts that I had collected thanks to a little research, as if it was a sort of dark romance. Then I cut it to keep it as sharp as possible.

Then, the composition of the show itself meant understanding how (and where and when and why) I could put together these two story lines and the music materials. And we can say that it was only than that the script was written: on me, together with the director.

M Do you think the way Nina’ s Drag Queens usually start from classic plays to rework them makes them fairly unique in the world of drag? Or did you have a model in mind when you started working in this way?

L It is of course very common to rewrite classical works in contemporary theatre. Most of the time it is probably done in a less visible way than ours, sometimes it is just the director’s point of view … and I think this is a healthy way to study a big story if you change it, open it up, so you can call it into question.

We had no specific models in mind when we started, we just wanted to have fun and were excited to discover something new about characters – the drag queens – who are usually connected exclusively with performative acts and cabaret.

In the end, I think that putting together drag world and classic plays created a very specific style and poetics … and the result is, yes, quite unique.

M Alessio Calciolari directs Alma – How do you work together to achieve what is a stunningly beautiful piece of total theatre?

L Thank you for the stunningly! Alessio began as a dancer and basically his vision is all about the body, and the body in space, so it was charming and challenging to understand with him how to give shape to my words onstage (in particular the Alma Mahler’s parts are very literary, by choice).

Together, rehearsal after rehearsal, we built this “metaphysical room”, a place where the two stories could cohabit. Alessio’s staging and my writing basically hinge on the question: how can they intertwine?

M When did you start working on costumes and set in the rehearsal process?

L We use very simple items, and most of them were there from the beginning (the carpet, the trolley bag, the armchair, some dresses). As we went along we simply changed some of them with something more functional or more beautiful, together with our set and costume designer Rosa Mariotti – who, for example, literally dressed the armchair.

M Are your costume and set designers people you normally work with?

L Yes, we usually have long-term collaborations. For example, Rosa is currently designing the costumes for our new production, Queen LeaR. Andrea Violato, who did the lighting design for Alma and built the lamps we use on stage, will also be part of Queen LeaR’s artistic team.

M Music is a key element in Alma. For Italians some of the music is virtually classical What do Ornella Vanoni and Patty Pravo mean to you?

L There are two very famous Italian song in Alma: “La bambola” by Patty Pravo (in a cover by Giusy Ferreri) and “Mi sono innamorato di te” by Luigi Tenco (in a cover by Ornella Vanoni, mixed with a Gustav Mahler’s symphony). The first is one of our most iconic pop songs, the other is one of the most romantic. Both of them strike a vibrant chord with Italian audiences.

For me these singers are part of our culture, using their voices in a show gives me the opportunity to establish a deep emotional bond with the audience and to make the story closer, creating a sort of “common language”.

M This is the first time you are doing a solo show? What are the challenges?

L My first time, yes. The challenge is the measure. Too much, to little. Usually you have stage pals to help you in find the balance, when you are alone is all on you…

At the same time, this is a deeply desired show, which had a long and organic creative process: so I know every detail and I feel at home while doing it. Moreover, it’s almost 2 years from Alma’s debut, so it has grown. The real challenge, now, is to do the show in English!

M In Italy, where there is no funding body like Creative Scotland or the English Arts Council, independent theatre companies like Nina’s Drag Queens struggle to survive. How did Nina’s Drag Queens manage to fund this show?

L Along with many initiatives and open calls we follow to find some resources, we just started a membership campaign.

Anyone can now sustain our company, becoming a Nina’s Sister, therefore part of the Sisterhood! We’re so proud of this project, that collects the energy of all our friends, fans, and pupils that in these first ten company years have followed and appreciated our work … so I’ll just close this nice chat saying something that I’ve repeated a lot in these last month: who finds a Sister finds a treasure!